Written by: Wendy Merritt (Australian National University)

The West Bengal Accelerated Development and Minor Irrigation Project (WBADMIP) aims to enhance agricultural production of small and marginal farmers in 19 districts across West Bengal, India. Key to WBADMIP is strengthening Water User Association (WUA) capacity to construct, operate and maintain minor irrigation schemes. In addition WBADMIP are providing agricultural services, encouraging crop diversification and use of new technologies, and creating income generating opportunities (http://www.wbadmip.org/).

In 2018 the WBADMIP and SIAGI project teams explored opportunities for sharing learnings of how to engage with and empower farmers and marginal communities to lead to transformational change in community water management and agriculture-based rural livelihoods. A one-day workshop was held in Kolkata in March 2018 where SIAGI outlined our work on ethical community engagement (ECE), bioeconomic modelling, inclusive value chains, and nutrition sensitive agriculture (NSA). PRADAN and CDHI continued engaging with WBADMIP over the following months, and the teams held a joint one-day workshop on 7 December 2018 to share experiences in working with marginalised farmers and establishing effective local institutions, and to test SIAGI’s ideas around principles and practice of ECE and scaling strategies for ECE.

Reflections on the WBADMIP

The decision of WBADMIP to partner with communities and NGOs was by necessity. WBADMIP had been working in the barren lands around Bankura and by 2015 the project was under pressure to complete the work in 3-4 months before it would be embargoed in the lead up to the state election. Rather than the normal route of engaging contractors WBADMIP had to empower the community to act. They engaged service providers (e.g. PRADAN and other NGOs) to work with community and WBADMIP to achieve the project goals. The experience working with community has been so rewarding that one participant said that ‘now we would choose to engage with community even if using a contractor’. During this workshop, the WBADMIP team reflected on their experiences in the Bankura and Jalpaiguri Districts in West Bengal, and why it had changed how they would choose to implement projects in the future.

WBADMIP activities on the barren lands in Bankura

The collaboration between WBADMIP, the WUA and PRADAN in Bankura District in West Bengal focused on the barren infertile lands that had received little attention from government in the past. The reality is that all the good land goes to the powerful and servicing this land with projects like WBADMIP does little for those who lack power and need help from the government. The WBADMIP leadership recognised that by going to the barren lands they are better able to reach the poor and the marginalised farming households.

The first meeting with community and PRADAN in Hakimsanin was an eye-opening experience for some in WBADMIP. One participant at the workshop noted that it ‘used to be hard to read people and that 10-15 years ago government people couldn’t even approach the village … now women were running the show and articulating what needed to be done and that with government resources they (the community) would do’. PRADAN had developed trust with the women in the community from past project activities and so when the women were eager to share responsibility for activities, the WBADMIP team were encouraged to believe the project could work.

The communities living on the barren, infertile lands have been heavily dependent on seasonal migration to generate household incomes. Under the WBADMIP project there has been a shift towards water harvesting to support cropping, horticulture and fisheries. Community spirits have raised, with some saying if this continues then they may not have to migrate in the future. The shift in actions and attitude of WUAs has been substantial. A few male members dominated initial meetings but this has changed to include more voices including those of women. The WUA are now thinking about schemes to capture surface water rather than the wells they initially wanted. The attitude of taking whatever government offers has changed to giving opinions and direction to government and proactively working to change their own situation. Tellingly, the Hakimsanin community have contributed funds from their Self Help Group (SHG) whilst waiting for funds from WBADMIP to arrive, an indication of their commitment to the project aims and their trust in the process, PRADAN and WBADMIP. The WUAs have strengthened their local governance and accountability, and women have taken charge of intercropping, reporting back to WBADMIP, and planning WUA roles and responsibilities.

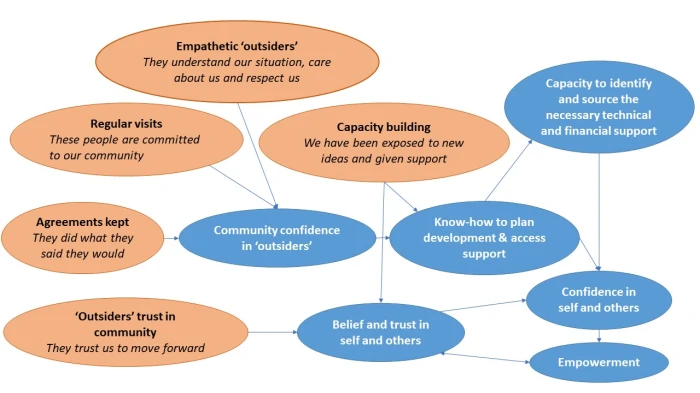

Captured in the diagram below is snapshot of how the actions and attitudes of WBADMIP and PRADAN (orange ovals) built community trust and confidence in themselves and others, and developed capacity of individuals and the WUA (blue ovals). Women in particular are being empowered to take charge though PRADANs focus on building the capacity of WUA members by conducting orientation programs, organising exposure visits, providing planning support for communities to drive development of their land and water resources, and by acting as a bridge between the community and WBADMIP. WBADMIP have demonstrated empathy, commitment; trust in community and accountability, which has encouraged community participation. Community told PRADAN that initially they were ‘scared about officials visiting, but then they saw genuine interest and so were confident to share’.

A key realisation for WBADMIP was the importance of shifting from large infrastructure to small water harvesting structures that women and marginalised farmers can themselves implement and maintain. Not only are these schemes cheaper, they have empowered communities to take charge. Working with the WUA to implement water harvesting interventions has proven more cost effective than would have been achieved using contractors. The community could save money by hiring equipment to prepare their land and doing the work themselves, rather than hiring contractors. WBADMIP are also saving money as a result.

WBADMIP activities in the Jalpaiguri district

Reflections on WBADMIP activities in the Jalpaiguri district centred around institutional linkages, capacity building and empowering community, and how to ‘exit’ the community. At a high level, WBADMIP feel that they ‘should not be the crutches for their community’, and if they are fair and transparent in how they work, then they will build trust and create an environment for community to empower themselves to develop sustainable livelihoods.

During a field visit on 5 December 2018, the SIAGI team noted how cohesive the local WBADMIP team were, and that they were impressed by the capacity of individual members to discuss with community issues that were outside their disciplinary background. In part this reflects the design of WBADMIP to cut across agriculture, fisheries, water and other agencies, but also the fact that small teams have to reach many (100+) WUAs, meaning they have to be across disciplines. In the workshop discussions, it was highlighted that building internal capacities of government or other institutions was critical for any cross-disciplinary project (like the WBADMIP) to be effective in partnering with community. This is not often achieved to the level seen in Jalpaiguri.

Much discussion centred on how to exit community at the end of a project. Strengthening inter-agency linkages was seen as a key outcome to be achieved before ‘exiting’ the community. One WBADMIP team member identified that their key challenge is to convince the WUA that WBADMIP is a short project after which they will have to look after themselves. Normally when they work with communities there is an expectation that the department will have a longer presence. Fostering trust is critical and building on community-respected service providers has been key to WBADMIP developing relationships with community. One striking comment was that ‘for this work [WBADMIP] we are not “diku” (outsider) … rather we are your people’.

Ethical Community Engagement

Principles and practices

The principles and practices of ECE distilled from the SIAGI project encapsulated many of the WBADMIP teams feelings based on experiences in the field. Being aware of these principles and practices will help them consider their activities more systematically and better understand why they do things the way they do and to help ‘unlearn’ the traditional approaches of how to engage with community. This has many parallels with management of complex socio-ecological systems such as the Great Barrier Reef. Having the mindset of ECE is one thing but how to do it is another question entirely, especially at large scales.

|

Principles of Ethical Community Engagement Individual and organisational values and cultures play a key role in inclusive practice.

Further information: https://siagi.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/siagi-report_ngo-practice_-report-for-mtr_final_july-2018.pdf |

Moving beyond a project – how to support more widespread impact with ECE

Taking an ECE approach in SIAGI has been intensive, and whilst it has proven critical to the project, we recognise that as a research project we have had the liberty to take the time to reflect with community and adapt our activities. This is a luxury that government agencies or NGOs typically do not have. Indeed, it was noted during the workshop that ‘Government are asked to do things at great scale, often quickly, and ECE in this environment is difficult terrain’. So how do WBADMIP or similar programs advance whilst keeping ECE principles in mind?

Scaling ECE in WBADMIP activities is really a way of formally recognising, and supporting, much of what WBDAMIP staff already try to do. Strategies for scaling of ECE outlined below include a mix of trying to support this across more locations (1,2); emphasising learning and capacity building for those facilitating ECE (3,4); and creating an enabling environment by building appreciation and capacity of those organisations designing and funding development programs to support ECE (5,6,7). To be successful, a range of these will be needed.

| Replication | 1. Simultaneously replicate the ECE process in more locations

2. Accelerate the ECE process |

| Investing in learning and capacity building | 3. Distributed train-the-trainer approaches

4. Developing a broader cohort of ECE service providers |

| Learning and capacity building / policy change | 5. Strengthen donor and government agency capacity (culture and value) in selecting appropriate ECE service providers |

| Creating an enabling environment | 6. Ensuring program design, implementation and evaluation metrics support ECE approach

7. Building strong collectives of women |

SIAGI and WBADMIP discussed what it would mean to apply ECE principles in the context of WBADMIP’s activities. The sheer volume of WUA and land targeted by WBADMIP, over such a short period of time, is an example of the “Replicating ECE in more locations”. There could be opportunities to engage with PRADAN to analyse where the successes have (or have not been) in the Bankura district in order to better understand the challenges of this approach. WBADMIP’s consideration of engaging service providers with a strong presence in an area in order to harness their relationships and their relationship with community is consistent with strategy 5. The potential of bring ECE principles and practices into program design, implementation and evaluation was noted (Strategy 6). Accelerating the ECE process (2) was contentious, and largely dismissed as inconsistent with core principles of ECE (eg. that community drive the engagement process and its timing).

Avenues for future collaboration

After a positive day reflecting upon the successes and challenges of both WBADMIP and SIAGI, clear synergies were identified. Many avenues exist to explore future collaborations, particularly exploring scaling strategies 5 to 7. Reflecting on the scaling process and applying lessons learnt through adaptive management will be critical in the coming year as the partnership between SIAGI partners and ADMIP progresses.